Now

that I have finished my Boston by Foot docent training and passed the final

(both written and verbal), it’s time to learn the tour that I have chosen to

give. Many different tours are offered

by @bostonbyfoot and there’s so much to know that learning to do one well

before branching out is the wisest course.

I chose the Victorian

Back Bay tour for several reasons.

The filling of the Back Bay is an engineering marvel that I find fascinating

along with the resulting construction requirements for all of the

nineteenth-century houses and many of the twentieth-century buildings.

When

the Puritans landed in 1630, Boston looked very different than it does

now. At that time, the Shawmut peninsula

was made up of three irregularly shaped lobes at the end of a long, narrow

neck. All together, there were no more

than 487 acres of habitable land on the peninsula and a fair amount of that was

taken up by hills. There was the TriMountain—Beacon

Hill, Pemberton Hill, and Mount Vernon—as well as Copp’s Hill and Fort

Hill.

Common wisdom blames

cow paths for Boston’s random street pattern but the poor cows have been

maligned. The first streets were laid

out by people who needed to go past the hills and around the three lobes while

on their way to important destinations like the harbor, the spring, the

pasture, the Town House, and the market. As land was filled in different

locations and at different times, more streets were created to fit the newly

created section. Nome of them fit into a

logical grid.

|

| View of the Back Bay from the State House on Beacon Hill |

These

487 acres met the town’s needs pretty well, although land making started early

along the waterfront. Fully one sixth of

Boston is built on made land. But things

changed in the nineteenth century when a variety of influences drove a need for

more land. Over that same period, the

Back Bay had been converted by damming and railroad causeways from shallow salt

marshes and mud flats on the tidal Charles River to a stagnant stinking

sewer. Everything went into it from

garbage and raw sewage to dead animals.

The tony families in their Beacon Hill homes found that Old

Mother West Wind had very bad breath.

Something had to be done. Something was done. A typical American combination of public need

and private enterprise resulted in the Tripartite Indenture, a settlement

reached by the City of Boston, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and the Boston

Water Power Company. Signed on December

11, 1856, it enabled the filling of the Back Bay to begin.

|

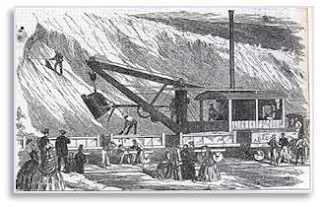

| Stationary Steam Shovel Filling Rail Cars |

Common wisdom says that the Back

Bay was filled in with the top of Beacon Hill but that’s not really the

case. The TriMountain, including Beacon

Hill, was indeed lowered by 60 feet and used as fill in other places but the Back

Bay’s New Land was created over 37 years with gravel from Needham, nine miles

away.

The project would not have gone

far, however, without the fortuitous invention of the steam shovel. These stationary devices loaded up to 35 rail

cars—drawn by equally new steam locomotives—in just five minutes and the trains

rolled in to a tipping point in the marsh 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The filling proceeded from the Public Garden

on the east to the Fenway area and created much more land than is currently

included in what is now called the Back Bay neighborhood. When it was done, Boston had grown by 570

acres.

For those who are interested,

the definitive book on the land making in Boston is Gaining

Ground by Nancy Seasholes, an historian and historical archaeologist. The book

is organized geographically and each chapter deals with a specific section

of Boston. It’s big, very detailed, packed

with information, and illustrated with lots of maps and photographs.

That would be a major project today

and even now we recognize it as an engineering marvel and an enormous

technological feat. Because the New Land

was flat and relatively straight, it had a logical pattern of boulevards and

cross streets. The streets are named

alphabetically, starting at the Public Garden: Arlington, Berkeley, Clarendon,

Dartmouth, Exeter, Fairfield, Gloucester, and Hereford.

Next came building on

the New Land, which was planned as a neighborhood of elegant homes for wealthy

Yankees. Unfortunately, the real estate

consisted of uncompacted gravel and that’s not a stable base for anything

bigger than a shed. How did they do

it? More later.

No comments:

Post a Comment