Denial

is powerful.

It’s

easy to just not see what we don’t like, don’t agree with, don’t want to

acknowledge, don’t want to admit, or don’t want to pay for. In America right now, I think we are in a

state of massive denial about our approach to mental illness.

When

I watched the news broadcasts about mass shootings from Virginia Tech to Aurora

to Newtown, I looked behind the killers to see parents in great distress. They knew their son was ill: not right,

disturbed, not himself, strange, unpredictable, possibly dangerous. My heart went out to them. They were struggling to cope with that

behavior and figure out what to do, how to help their son while protecting the

rest of the family from his behavior—and doing it pretty much on their

own. Today, very little help is

available to people who need to deal with mentally disturbed family

members. Exactly how little there is has

been documented in an article in the June issue of Mother Jones by Mac McClelland entitled, “Schizophrenic.

Killer. My Cousin.”

It’s

a long article, but riveting. Also very

frightening.

Resources for treatment of

mental illness in America have been declining since 1963, two years after a

joint commission of the American Medical and American Psychiatric associations

recommended removing the mentally ill from large institutions and mainstreaming

them into society. Patients were

supposed to receive outpatient care from community services in local facilities

such as half-way houses. It sounded like

a good solution to folks on the left, who believed that people with mental

problems "should not be committed, medicated, or treated against their will

unless they’re a danger to themselves or to others." It sounded great to folks on the right who

wanted to reduce the size of government and lower everyone’s taxes. But a funny thing happened on the way to

mainstream utopia: states opened the doors

of their mental hospitals a lot faster than anyone expected and the community

resources to replace them were never hired, built, or funded.

|

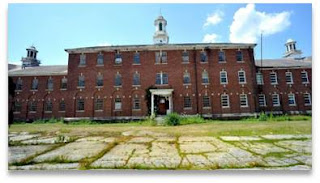

| Fairfield Hills State Hospital in Newtown, CT |

It's

ironic that Newtown, Connecticut was once the location of Fairfield

Hills State Hospital, a psychiatric hospital that housed 4,000

patients--and also employed 20 doctors, 50 nurses and 100 other employees. It was created in 1931 due to overcrowding at two other state hospitals and closed in December, 1995.

So

where do the mentally ill go today? Into the

streets, onto heating grates, under overpasses, into homeless shelters, and—most

of all—into jail. When faced with a

child whose behavior has become erratic, unpredictable, sometimes violent and

increasingly dangerous, parents often have no option but to call the

police. Law enforcement has become a

path of admission to psychiatric facilities, should any still exist near the

family or have room to take in someone new.

Often the case is neither.

Here’s

where one kind of denial kicks in. Parents

have enough trouble admitting that their son is ill and possibly dangerous to

himself, to them, to his siblings or to his classmates. It’s a tough line for anyone to cross. To then have to call the cops on your own kid

triggers a stronger denial, one that says, “We can take care of it,” or

“He’s not that bad—yet.” It takes a

special kind of clear thinking to pick up that phone and watch your son being

taken away in handcuffs.

What

makes it worse is that the statistics are not good for mental patients in

police custody. Law enforcement officers

are, after all, not educated, trained or equipped to handle the mentally

ill. They aren’t doctors or social

workers. They have guns, not

psycho-active drugs.

So

parents try to keep the lid on, struggling harder and harder every day until things

finally blow up. What happens next is

something Psychiatrist E. Fuller Torrey calls, “a predictable tragedy.” It’s a

term he applies to, “the Gabrielle Giffords shooting the Virginia Tech massacre,

the Aurora movie theater shooting, the Sandy Hook elementary school shooting,

and dozens of other recent homicides, some of them famous mass killings or

subway platform shovings, but many of them less publicized.” Dr. Torrey estimates—conservatively—that 10%

of US homicides are committed by the severely mentally ill who go untreated.

|

| Gabrielle Giffords Testifies in Congress |

There’s

a price to be paid for America’s second kind of denial, that of the need to treat the

mentally ill, and many people are paying it every day. They include the mentally ill themselves as well

as those close to them. We can as a country

stick our heads in the sand and refuse to pay for doctors, treatment

facilities, social workers, and medication.

But we’d still be kidding ourselves.

McClelland’s article makes the point that jailing our mentally ill is

not cheap. In it, Randall Hagar, director

of government relations for the California Psychiatric Association, says, “Two

to three thousand dollars in treatment saves $50,000 in jail.” And that’s just the cost of

incarceration. What about medical costs

for people who have been injured? How

much did it cost for just Gabby Gifford’s treatment and therapy? What about funeral costs for those who have

been killed? Does anyone total up what we pay as citizens and as a country as a result of such violence?

Some

people who read this might think it’s not something we should be talking

about. They might chastise me for

stigmatizing the mentally ill, which is not my intention. Denial doesn’t solve problems and we have a big problem in this country. I’m glad that Mac McClelland wrote this article

and @Motherjones published it Because ignoring our problem with the untreated mentally ill has only made it worse and

bigger. Continuing to ignore it will

bring us more predictable tragedies.

No comments:

Post a Comment